rustrays

1 RustRays Overview

This is my attempt at following the excellent book by Peter Shirley, Raytracing In One Weekend, implemented in Rust.

I am a new Rustacean. In fact, this is my first Rust program. After starting the book without any Rust knowledge, I realized I wanted to implement this in the “Rust” way as much as possible. Therefore, I took a pause from implementation, read The Rust Book, then started again.

Where I’ve found a particular change necessary for Rust, or noticed some improvements by implementing in Rust, I note this in comments.

2 Output an Image

First up, is generating an image. In his C++ implementation, Peter S. uses static casting to output integer r, g, and b values with a dynamic range 0 - 255.999. In my implementation of a Color structure, I implement the Display trait to output PPM formated color pixel values. I have a DYN_RANGE and MAX_VAL constants to perform the normalization to a 0 - 255.999 range from 0.0 - 1.0.

pub const DYN_RANGE: i32 = 256;

const MAX_VAL: f32 = DYN_RANGE as f32 - 0.001;

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Default)]

pub struct Color {

pub r: f32,

pub g: f32,

pub b: f32

}

impl std::fmt::Display for Color {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut std::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> std::fmt::Result {

write!(f, "{}, {}, {}", (self.r.clamp(0.0, 0.999)*MAX_VAL) as u32,

(self.g.clamp(0.0, 0.999)*MAX_VAL) as u32,

(self.b.clamp(0.0, 0.999)*MAX_VAL) as u32)

}

}

3 The Vector3 Class

My first real “Idiomatic Rust” quandary was whether to implement the Vector3 and Color as separate structures or aliased, like the original author. This became apparent as I didn’t like Rust’s aliasing capabilities (made it seem clunky), and I wanted to get Color operations that made sense for colors, but as methods, rather than utility functions. I had to implement many operations twice, which can be hard to maintain, but how often will I need to change how the + operation works?

Furthermore, I actually spent more time trying to determine how to handle Vectors vs Points. I liked the idea of being able to distinguise based on how they are used, but implementing them twice was aweful. I decided to just implement Vector3, and never use Point. Variable names of type Vector3 that are used as points can be inferred by their name, such as location.

One consequence of this decision is that I had to implement casting methods for Color and Vector3 so I could convert between them when needed. This mainly comes into play when you want to color a surface based on normals.

pub fn ray_color_normals(r: &Ray, world: &impl Hittable) -> Color {

match world.hit(r, 0.0, INFINITY) {

None => return ray_color_bg(r),

Some(hit_record) => {

return 0.5 * (Color::from_vector(hit_record.normal) + Color::new(1.0,1.0,1.0,));

},

}

}

4 Rays, Camera, Background!

This is where I hit my first snag with borrowing and mutability. I originally implemented the at(t) function as I would with any languange:

pub struct Ray {

pub origin: Point3,

pub direction: Vector3

}

impl Ray {

pub fn at(self, t: f32) -> Point3 {

self.origin + t*self.direction

}

}

5 Adding a Sphere

This section was relatively straight-forward in Rust, even as a new Rustacean. Since I had read the Ray Tracing In One Weekend through a couple times, I did split the implementation of the ray_color function into a background and the sphere at this point. This made it easier to move to hittables and sphere objects.

6 Surface Normals and Hittable Objects

I can create rays and find a location at t. However, this quickly fell apart when using this in the context of a hittable object (implemented as a Hittable trait).

impl Hittable for Sphere {

fn hit(&self, r: &Ray, t_min: f32, t_max: f32) -> Option<HitRecord> {

//find root

//...

let p = r.at(root);

let outward_normal = (p - self.center)/self.radius;

let front_face = r.direction.dot(outward_normal) < 0.0;

let normal = if front_face {outward_normal} else {-outward_normal};

Some(HitRecord {t:root, p:p, normal:normal, front_face: false})

}

}

I pass in the ray as an immutable reference because I don’t need to change the ray, but only use it to find where it lands. However, since my ‘at’ method has self as a mutable value, issues ensued because here I accept the ray as an immutable reference. There were a few more steps I glossed over, but essentially, I had to make the ‘at’ method use an immutable reference such that I could call it on borrowed references of Ray.

impl Ray {

pub fn at(&self, t: f32) -> Point3 { // had to use &self to make it an unmutable reference to self, so this could be called by borrowers of *self

self.origin + t*self.direction

}

}

I also learned about using Option enums to avoid the need to have the hit record returned through a argument. I have to say, this was refreshing at first, then felt a little verbose due to the return value handling, but eventually I came to really like this methodology. This made for a nice implementation of hittable list.

impl Hittable for HittableList {

fn hit(&self, r: &Ray, t_min: f32, t_max: f32) -> Option<HitRecord> {

let mut temp_rec = None;

//Was able to remove "hit_anything" because that logic is encapsulated in the use of Option<>, yay Rust!

let mut closest_so_far = t_max;

for hittable in &self.hittables {

match hittable.hit(r, t_min, closest_so_far) {

None => (),

Some(hit_record) => {

closest_so_far = hit_record.t;

temp_rec = Some(hit_record);

}

}

}

temp_rec

}

}

I was very relieved when I got to the Shared Pointers section of the tutorial because I am using Rust. Due to this fact, keeping track of ownership, lifetimes, and releasing memory is built into the language and no library is needed. Furthermore, Rust will prevent me from making mistakes in using such a library at compile time, which ensures correctness and safety, if adding a bit of complexity as a beginner.

7

I honestly spend more time than I thought I would on random utility functions. Rust’s support for random numbers was different than other languages I’ve used, so there was a bit of a learn curve. Ultimately, I used the thread_rng utility as the base random generator and built on that. After that, it was straighforward to implement the random vectors and unit vectors needed using functionality I had already implemented in my structs.

// Produce a random float [0,1)

pub fn rand() -> f32 {

thread_rng().gen_range(0.0..1.0)

}

// Produce a random float [min,max)

pub fn rand_range(min:f32, max:f32) -> f32 {

thread_rng().gen_range(min..max)

}

During implementation of the Camera object is when I ran into much of the reference and borrowing issues of the Ray struct. It is here that I decided I didn’t want the Ray struct to implement Copy because it is becoming a more complex object. I had to be careful when using these objects and implementing methods (such as useing &self). After this, implementing the actual Camera struct was a relatively straighforward port from C++.

When implementing the clamping and pixel sampling, I deviated slightly from the tutorial. Since I was using the Display train on a Color object to print out colors, I did not incorporate the samples per pixel into this trait, but did implement clamping within that trait:

impl std::fmt::Display for Color {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut std::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> std::fmt::Result {

write!(f, "{}, {}, {}", (self.r.clamp(0.0, 0.999)*MAX_VAL) as u32,

(self.g.clamp(0.0, 0.999)*MAX_VAL) as u32,

(self.b.clamp(0.0, 0.999)*MAX_VAL) as u32)

}

}

For sampling, I simply put it into the render function (which I pulled out of main into my utility module):

pub fn output_sphere_on_sphere() {

// image properties

const ASPECT_RATIO: f32 = 16.0 / 9.0;

const IMAGE_WIDTH: u32 = 400;

const IMAGE_HEIGHT: u32 = (IMAGE_WIDTH as f32 / ASPECT_RATIO) as u32;

const SAMPLES_PER_PIXEL: u32 = 100;

const MAX_DEPTH: u32 = 50;

// World

let mut world = HittableList::default();

world.add(Box::new(Sphere{center: Vector3::new(0.0,0.0,-1.0), radius: 0.5}));

world.add(Box::new(Sphere{center: Vector3::new(0.0,-100.5,-1.0), radius: 100.0}));

// Camera

let cam = Camera::new();

// Render Image

println!("P3");

println!("{} {}", IMAGE_WIDTH, IMAGE_HEIGHT);

println!("{}", (DYN_RANGE-1) as u32);

for j in (0..IMAGE_HEIGHT).rev() {

eprintln!("\nScanlines remaining: {} ", j);

for i in 0..IMAGE_WIDTH {

let mut pixel_color = Color::new(0.0,0.0,0.0);

for _s in 0..SAMPLES_PER_PIXEL {

let u = (i as f32 + rand())/(IMAGE_WIDTH as f32 - 1.0);

let v = (j as f32 + rand())/(IMAGE_HEIGHT as f32 - 1.0);

let r = cam.get_ray(u, v);

pixel_color += ray_color_bounce(&r, &world, MAX_DEPTH);

}

pixel_color /= SAMPLES_PER_PIXEL as f32;

pixel_color.gamma_correct();

println!("{}", pixel_color);

}

}

}

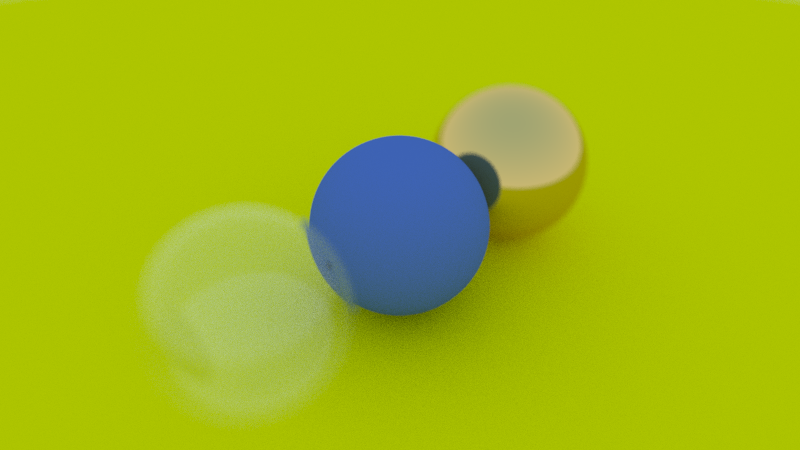

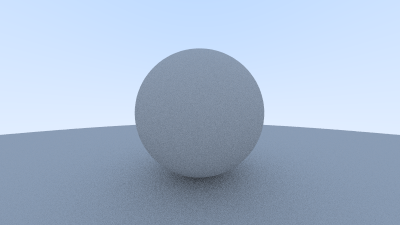

8 Simple Diffuse

I implement a diffuse material manually by reimplementing my color function as ray_color_bounce(), as used above. I went straight to implementing a lambertian diffuse material using a function to calculate a new ray based on a hit record and randome point in a sphere offset by the normal:

pub fn rand_lamb_vector(hit_record: HitRecord) -> Vector3 {

hit_record.p + hit_record.normal + rand_in_unit_sphere().unit_vector()

}

pub fn ray_color_bounce(r: &Ray, world: &impl Hittable, depth: u32) -> Color {

if depth <= 0 {

return Color::new(0.0,0.0,0.0);

}

match world.hit(r, 0.001, INFINITY) {

None => return ray_color_bg(r),

Some(hit_record) => {

let target = rand_lamb_vector(hit_record);

return 0.5 * ray_color_bounce(&Ray{origin:hit_record.p, direction:target-hit_record.p}, world, depth-1)

},

}

}

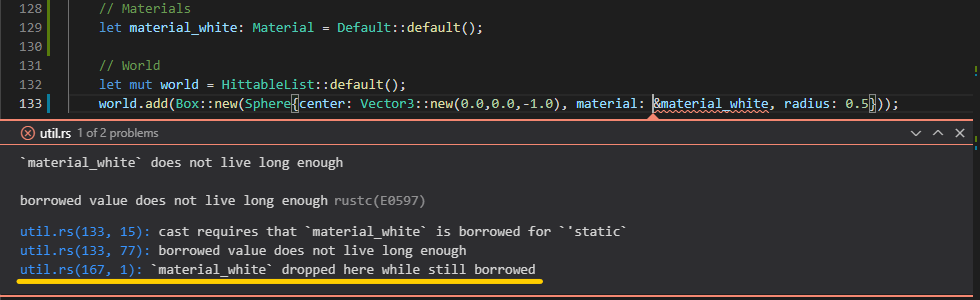

9 Metal and Materials

I decided to use an enum to implement materials. I went back and forth between using traits and enums, but at the very least, I wanted to learn how to use enums and this was the perfect place. I immediately ran into problems. I wanted to add a reference to my new material to my HitRecord (I want a reference because the same material may be in multiple objects and hit records).

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Default)]

pub struct HitRecord<'a> {

pub p: Vector3,

pub normal: Vector3,

pub material: &'a Material,

pub t: f32,

pub front_face: bool,

}

However, since I derived Default for this struct, Rust wanted me to implement the Default trait for &Material, which lead me down the rabbit hole of unsafe and `static code. After researching, I believe that the Default trait really should only be used for values that are wholly owned (meaning they contain only owned values). This makes sense as it eliminates the need to return new, initialized memory references from a function (memory leak, anyone?).

So, I simply had to remove the derive Default and make sure and initialize hit records explicitly with a previously created material. This, consequently, helps to enforce the lifetime requirements of my structs containing Material references.

My next lifetime issue was when I placed multiple “Hittable” objects in a vector for my world. I Boxed them up based on some online resources, but Box requires ‘static lifetime contents, so it did not like my material reference that was on the stack. I found a great answers here and here, but three years is a long time for Rust to change. I’m trying to avoid using any previous raytracing implementations to keep my ideas my own, but this illustrated my issue perfectly.

My initial solution is simple enough – add lifetimes to the HittableList to show that the Box inside the Vector only lasts as long as the HittableLIst. This removes the ‘static lifetime on Box, allowing the materials to live at least as long as the Box created for the Sphere to go inside the HittableList Vector. Clear as mud, right?

#[derive(Default)]

pub struct HittableList <'a> {

pub hittables : Vec<Box<dyn Hittable + 'a>>,

}

impl <'a> HittableList <'a> {

pub fn clear(&mut self) {

self.hittables.clear();

}

pub fn add(&mut self, p: Box<dyn Hittable + 'a>) { // Had to use Box<> because trait is dynamic and therefore size isn't known at compile time

self.hittables.push(p);

}

}

impl Hittable for HittableList <'_> {

fn hit(&self, r: &Ray, t_min: f32, t_max: f32) -> Option<HitRecord> {

let mut temp_rec = None;

//Was able to remove "hit_anything" because that logic is encapsulated in the use of Option<>, yay Rust!

let mut closest_so_far = t_max;

for hittable in &self.hittables {

match hittable.hit(r, t_min, closest_so_far) {

None => (),

Some(hit_record) => {

closest_so_far = hit_record.t;

temp_rec = Some(hit_record);

}

}

}

temp_rec

}

}

Once everything compiled again, I noticed a significant decrease in performance. Dynamic execution or too much memory copying?

The answer… don’t know yet, but for now, I’m moving onto general material implementation before I get into performance and profiling.

9 Materials (For Real This Time)

Refactoring the Hittable List and Primitives implementation was a whirlwind education in lifetimes and borrowing. I still don’t know if I grasp it fully, and I still don’t like the Box, but we are moving on and maybe in Rust 2021 I will find a solution that sits well with me.

First up for the material is to implement the scatter function. It is interesting that Rust’s NON-object-oriented programming approach really shows you where polymorphism can impact performance. I decided to use an enum to implement my material to all for a simple reference to such a material no matter what type (at this point, just metal or diffuse). I quickly realized that my reason for avoiding a material trait implemented by multiple structs really does a similar thing, but hides the dynamic execution into the dyn keyword, whereas I have to explicitly implement this in a match statement on the enum.

match self {

Self::Diffuse { albedo } => {

let mut scatter_dir = rand_lamb_vector(rec);

if scatter_dir.near_zero() {

scatter_dir = rec.normal;

};

let scattered = Ray { origin: rec.p, direction: scatter_dir};

(*albedo, scattered)

}

Self::Metal { albedo } => {

let reflected = r.direction.unit_vector().reflect(rec.normal);

let scattered = Ray{origin: rec.p, direction: reflected};

(*albedo, scattered)

}

}

I think it is great! Rust is forcing me to recognize and deal with all the impacts of my coding decisions. I will continue on this path, but it may be interesting to see if there is a big performace difference between implementing it as an enum, and branching to metal or diffuse calculations, or simply generalizing the material and having parameters null out diffuse or metal properties.

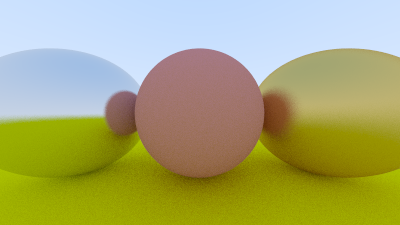

10 Dielectrics

It wasn’t until I starting implementing Dielectrics that I actually understood the normals direction and implications it had on processing and whether it is done at geometry or lighting time. The biggest trouble I had with implemention was simply math transcription. Many of rust’s math funciton (abs, sqrt) are implemented as member functions of base numeric types. This makes the code look more like reverse polish notation than the original equation and C implementation (hello 9th grade and the TI vs HP debate).

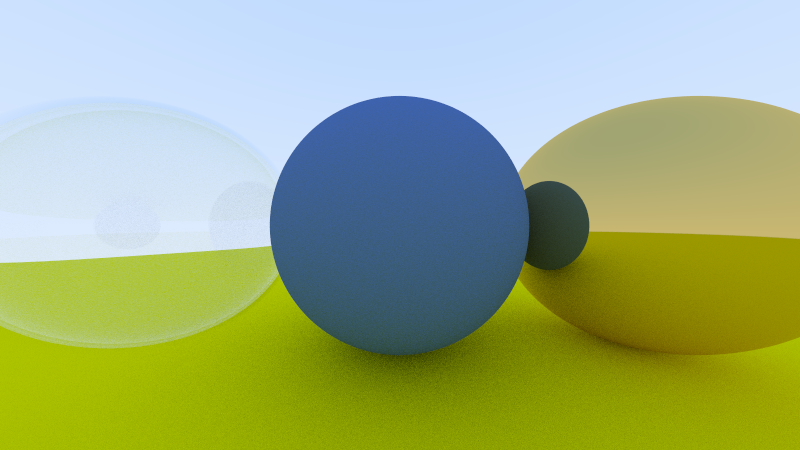

Adding the inner sphere to make a hollow sphere gave me an unexpected (but correct) result. The refraction inside the glass part of the sphere caused more distortion than I anticipated. Making the glass ball with a thinner shell (outer sphere radius 0.5 and inner radius 0.48) made it look more like I envisioned.

11 Camera

Most of the camera I already implemented as part of previous sessions, but this added positionability and field of view.

12 Defocus Blur

Relatively simple to implement based on the book, but will take more thought to gain intuition for focus distance and the math there.